How Regulation by Litigation Strangled American Abundance

Environmentalists aren't blocking housing. Wealthy homeowners are.

On an August morning in 2022, construction crews arrived at Berkeley’s historic People’s Park to do what countless students had been begging the University of California to do for years: build more housing. The university had a plan: 1,100 badly needed student beds and 125 units of supportive housing for the homeless, squeezed into one of the most expensive rental markets in the country.

Environmental review? Complete. Community input? Years of it. Local approval? Check.

For a moment, it looked like progress. Protesters tried to physically halt the work, tearing down fences and swarming the site, but they failed. Then the courts stepped in.

The bulldozers went silent. Toppled fencing and felled trees cluttered the grounds, a testament to how easily the machinery of the law can bring the physical world to a standstill. Students wondered whether the university had changed its mind again. It hadn’t. But a handful of local homeowners had found the power to stop it.

They invoked California’s Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to sue on the grounds that the university failed to adequately study environmental impacts. The claim was surreal: that the sound of students living—talking, laughing, socializing—should be legally classified as pollution.

Incredibly, the court agreed, ruling that “loud student parties” were indeed an environmental impact requiring mitigation. As Governor Gavin Newsom later put it, “a few wealthy Berkeley homeowners” had successfully weaponized state law to block housing for thousands.

The lawsuit froze construction for nearly two years. Emergency legislation had to be introduced in Sacramento. By the time the California Supreme Court finally stepped in to clarify that drunk students do not constitute an environmental impact, millions had been added to the project’s cost and thousands of students had spent another year scrambling for a place to live.

The story of People’s Park captures something essential about how modern America works and how it doesn’t. Our most urgent challenges to growth, from housing to infrastructure to clean energy, do not fail for lack of political will or administrative approval. They fail by attrition. They are funneled into a legal gauntlet where the friction of procedure—the delay, the cost, the uncertainty—becomes a prohibitive tax on progress.

What’s more, the specter of litigation often stops progress before it even starts. The mere anticipation of a lawsuit can chill innovation, deter investment, and prevent badly needed projects from ever breaking ground. Even when local agencies do try to build, the red tape they impose is rarely driven by genuine environmental concern, but by a desire to insulate themselves from future legal challenges. Cities bury themselves in bureaucracy not to please planners, but to preempt plaintiffs.

Scarcity in America is manufactured not mainly by environmentalists or bureaucrats, but by a litigation-centric legal system that empowers wealthy gatekeepers to block growth. We often blame bureaucrats or red tape for the country’s paralysis. But the fault lies less in the rules than in who has the resources to weaponize them.

II. Scarcity is Manufactured by The Courts, Not Bureaucrats

A growing movement of abundance thinkers, popularized by writers like Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, has diagnosed the symptom: America has become stunningly bad at building things. But the diagnosis often stops at red tape or bureaucracy. This misses the deeper, structural rot. The problem isn’t just that the rules are strict; it is that the mechanism of enforcing them has shifted from the agency to the courtroom.

The abundance framing has resonated across the political spectrum. Progressive supply-siders—and the YIMBY groups led by young progressives that have become one of the most inspiring political movements of the era—argue that a prosperous, decarbonized future requires building at a scale Americans haven’t seen since the postwar boom. Centrists see the inability to build as a crisis of state capacity and economic competitiveness. Conservative reformers point to red tape and administrative sprawl as evidence of government dysfunction. Everyone agrees that something is broken.

But Klein and Thompson’s deeper point is often misunderstood. The problem isn’t that government is too big. It’s that its structure has become brittle, encrusted with procedural demands that make decisive action nearly impossible.

The abundance literature focuses mostly on administrative permitting: environmental reviews, zoning boards, public comment requirements. But beneath these administrative hurdles lies a more foundational choke point, one that shapes how every regulation operates.

That choke point is the courts.

America did not always govern this way. The pivotal moment came in 1970, when Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The law required federal agencies to assess the environmental consequences of major actions, a new concept at the time but one broadly supported.

Agencies initially treated it as a paperwork exercise. Then came the 1971 case Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Committee v. Atomic Energy Commission, in which the D.C. Circuit Court declared that NEPA’s review obligations were “judicially enforceable.” Overnight, NEPA transformed from an administrative duty into a litigation engine.

Environmental review was no longer just a task for agencies; it was a weapon for citizens.

California passed its own version, CEQA, the same year. When Governor Ronald Reagan signed it, the law applied only to public projects. It was modest, cautious, and bureaucratic.

Then, in 1972, in a case called Friends of Mammoth v. Board of Supervisors, the California Supreme Court expanded CEQA’s reach to the entire private economy. The ruling subjected every private project requiring a permit—from shopping centers to condo buildings—to environmental review, and therefore to potential lawsuits.

The decision stunned lawmakers. San Francisco froze all building permits. The legislature imposed an emergency moratorium while it scrambled to react. California agencies suddenly found themselves overwhelmed with environmental impact reviews, as virtually every private development requiring a permit now triggered CEQA’s requirements.

The seismic shift wasn’t the requirement to review. It was the invitation to sue.

While CEQA is the most extreme example of litigation-driven policymaking, the pattern exists nationally. Under the federal NEPA, courts—not agencies—often determine whether major projects can move forward. A recent review found that federal agencies won roughly 80 percent of NEPA cases in 2022, yet even successful projects spent years in procedural battles over modeling assumptions, alternatives, and data adequacy. The litigation itself becomes the regulatory process. NEPA shows how judicialized environmental review operates when confined to federal megaprojects; CEQA shows what happens when that model is extended to every housing development and transit line in a state.

What had been a system of administrative judgment became a system of adversarial legal combat, where success depended not on environmental science but on the ability to hire counsel and endure years of uncertainty. America became a place where environmental regulation was not primarily made by agencies but by courts—and where any sufficiently motivated opponent could weaponize procedure to block growth.

This is “regulation by litigation” in action. The legislature passed a reasonable environmental measure. Then the courts decided that what was meant to be regulated would instead be endlessly litigated.

III. Who Actually Uses These Laws to Block Projects?

The common belief is that environmentalists—green nonprofits, activists, conservationists—are the main users of CEQA lawsuits. They are the villains in many abundance narratives, the foot soldiers of procedural obstruction.

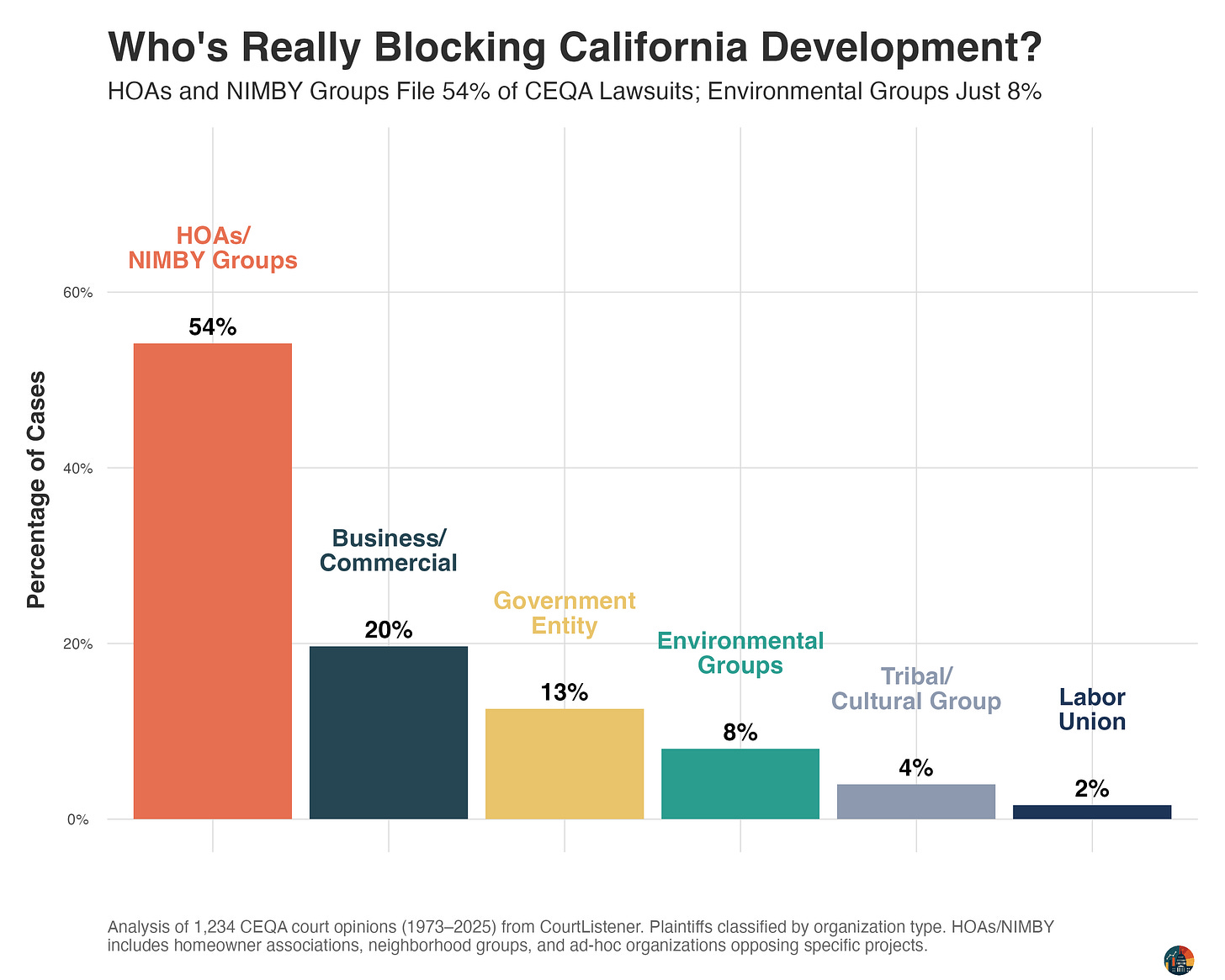

The narrative is that environmental law pits public-interest crusaders against corporate polluters. But the data tells a different story. In an analysis of 1,234 CEQA cases covering the period from 1973 to 2025, I found that established environmental organizations accounted for only about 8 percent of lawsuits.

When genuine environmental groups sue, they look nothing like the obstructionist caricatures they are often painted as. The Sierra Club challenged groundwater extraction that threatened regional aquifers; the Center for Biological Diversity fought to protect the unarmored threespine stickleback; the Cleveland National Forest Foundation litigated over countywide emissions. Their lawsuits focused primarily on ecosystems, climate, and public health.

Moreover, these organizations tend to concentrate on rural projects where the ecological stakes are high. When it comes to the lawsuits that are actually killing housing abundance in our cities, environmental groups are simply not there. They rarely challenge housing projects. When they do, it’s not apartment buildings in city centers but rather massive subdivisions on the urban fringe that would convert thousands of acres of wildland into sprawl.

The docket is instead crowded by a different kind of plaintiff: homeowners associations, wealthy individuals, and ad hoc community groups formed solely to oppose specific projects. Groups with names like “Save Lafayette Trees” appear repeatedly, sounding like conservationists but acting like property defenders. While established environmental groups fight for wetlands and water safety, these local groups target infill housing and mixed-use developments in neighborhoods that are already paved. Their concerns are almost exclusively local, private, and property-oriented.

In Marin County, a local HOA sued to block affordable senior housing, citing strained concerns about ambulance emissions and “social congregation impacts.” Meeting minutes revealed the true motivation was a fear regarding property values and demographic change. The developer ultimately abandoned the project; luxury townhouses, which faced no opposition, were built instead.

In another instance, a homeowner opposing a new apartment building argued that it would diminish the value of a Victorian he had renovated and hoped to convert into a bed-and-breakfast. Elsewhere, a group of neighbors raised concerns about the loss of sunlight, privacy, and parking, complaints the court bluntly categorized as personal NIMBY interests. Sometimes, this legal creativity borders on the absurd. Opponents of a Planned Parenthood clinic argued that protests outside the facility would generate “environmental impacts.” The case failed, but not before causing years of delay.

HOAs are hardly bastions of left-wing environmental radicalism. They are some of the most structurally conservative, exclusionary institutions in American civic life, “little platoons” of property defense. Yet, they remain among the most prolific users of environmental regulations.

For the modern obstructionist, zoning and litigation are a two-front war. Their first line of defense is the zoning board, where they fight to maintain bans on apartments or mixed-use buildings. But as the YIMBY movement succeeds in legalizing density—as California recently did by ending exclusive single-family zoning—these groups have simply retreated to their second line of defense: the courtroom. They don’t need to win on the merits; they just need to impose enough delay to kill the project’s financing

Businesses and commercial entities file twice as many lawsuits as environmental groups, yet their motives rarely concern conservation. Instead, they weaponize the law in two distinct ways.

First, they use CEQA to stifle competition. In one egregious example, a gas station owner sued to block a competitor’s expansion across the street, using inflated emissions concerns as legal cover. In a remarkable federal case, a hotel developer alleged that its rival used environmental challenges as a form of extortion, essentially saying, pay us or we’ll keep suing.

Second, and most frequently, businesses employ a tactic known as “reverse CEQA” to block environmental regulation. Challenging new rules is the single most common reason businesses file CEQA lawsuits. Oil refineries and paint manufacturers sue air quality management districts, arguing that mandatory pollution scrubbers would consume excessive water, or that “eco-friendly” low-emission paints are so nondurable they would actually increase waste. In one instance, a plastic bag manufacturer’s coalition even sued Manhattan Beach over its bag ban, arguing that paper bags had environmental impacts requiring review.

Finally, in a surprising number of cases, public agencies use taxpayer dollars to sue other public agencies—cities suing counties over jail expansions, school districts suing cities over new apartments—using environmental law as a tool for inter-agency turf wars.

Rather than having to form a community group and raise their own legal funds, opponents simply pressure their local officials to weaponize the city attorney against the project. The result is a perverse loop where taxpayers fund the construction of public infrastructure, and then fund the lawsuit to stop it. Consider the spectacle of the Beverly Hills Unified School District and the City of Beverly Hills suing the L.A. Metropolitan Transportation Authority to block a subway tunnel. While their lawsuit invoked high-minded concerns about seismic risks and air quality, the administrative record revealed a more candid motivation: fears of “decreased value in homeowners’ properties.”

Environmental law has become a tool disproportionately wielded by the wealthy against growth in affluent areas, while the places suffering the worst environmental harms often lack the legal firepower to fight the pollution they actually endure. This is not a story about environmentalism gone too far. It is a story about a legal system that has become a machine for entrenching wealth and power.

IV. American Regulation is a Lawyer’s Economy

What ties these stories together is the economics of lawyering. As Francis Fukuyama has argued, America’s “judicialization of functions that in other developed democracies are handled by administrative bureaucracies has led to an explosion of costly litigation, slow decision-making, and highly inconsistent enforcement of laws.” Compared to Germany or Japan, where specialized tribunals resolve planning disputes in months, America routes everything through courts that can take years.

Our system of proceduralism creates a vast economy for the legal profession. Every extra step—new filings, new appeals, new injunctions—generates billable hours. The incentives are structurally misaligned: what enriches lawyers and empowers the fortunate few who can afford their services imposes scarcity on everyone else. The result is a peculiar form of regulatory capture: not by industry, but by the legal industry itself.

This dynamic has roots in the legal progressivism movement of the 1970s. When Ralph Nader’s activists pioneered the litigation-centered model of governance, the goal was to check corporate power. But the tools forged by activists to fight polluters and check corporate power are now sold to the highest bidder to check public progress.

My research on the legal profession shows that American lawyers as a group are left-leaning but the outcomes they produce for their paying clients generally are not. They preside over a regulatory system that is structurally conservative, designed to preserve the status quo and protect wealth.

Critics might argue that litigation provides essential checks on development. Without the ability to sue, wouldn’t developers run roughshod over communities?

This is a fair concern, but the current system doesn’t actually protect the vulnerable—it empowers the wealthy. A Marin County HOA can spend years litigating against ambulance emissions. The communities most harmed by pollution—poor, largely nonwhite neighborhoods in California’s Central Valley or South Coast air basins—lack the resources and legal firepower to fight the pollution they actually endure.

The consequence is a distinctly American form of scarcity: a political economy in which delay is easy, judicial review is expansive, and building anything—from a wind farm to a subway station—requires surviving a gauntlet designed for maximum contestation and minimal resolution.

V. The Abundance Agenda Begins With Legal Reform

If abundance means building more—more housing, more transit, more clean energy—then the first step is to reform the legal system that makes building slower, costlier, and riskier than it needs to be. The goal of reform should not be to abolish environmental review, but to distinguish legitimate environmental stewardship from legal gamesmanship. This requires a fundamental restructuring of who can sue, where they sue, and what happens when they lose.

The most critical gatekeeping mechanism is standing, the right to bring a lawsuit. Today, standing under laws like CEQA is effectively universal, allowing anyone with a grievance to halt a project. A functioning system would limit this right to those protecting the genuine public interest, rather than private property. This requirement is the key to ending the plague of pop-up NIMBY groups and business competitors who masquerade as environmentalists to settle private scores. If a project genuinely threatens an ecosystem, the suit should be allowed; a neighbor worried about their view of the bay should not be granted the same legal weapon.

California took a significant step this summer when Governor Newsom signed AB 130 and SB 131, exempting most urban infill housing from CEQA—the most consequential reform to the law in over fifty years. For qualifying projects, it eliminates the litigation threat entirely. But the fix is narrow. Broader clean energy projects, transmission lines, commercial development, and any housing that opponents can claim to a sympathetic judge doesn’t fit the criteria remain exposed. And the broader legal architecture—universal standing, generalist courts, one-way fee shifting—is unchanged. Exemptions carve out categories; they do not reform the system that makes litigation so potent a weapon.

But the fix is narrow. Transit projects, clean energy infrastructure, commercial development, and housing that doesn’t qualify remain exposed to the same system of indefinite delay. And the broader legal architecture—universal standing, generalist courts, one-way fee shifting—is unchanged. Exemptions carve out categories; they do not reform the system that makes litigation so potent a weapon.

Beyond limiting who can sue, we must change where these disputes are heard. America stands alone among developed democracies in asking generalist judges to decipher complex ecological modeling on open-ended timelines. Land-use disputes should be removed from the general court system and routed to specialized administrative bodies staffed with experts in planning, ecology, and engineering. Because these decision-makers possess subject-matter fluency, they can distinguish technical errors from substantive harms in weeks rather than years. This would create a dedicated express lane for review that prioritizes scientific competence over procedural wrangling.

When litigation does occur, it must cease to be a tool of indefinite delay. We must end the practice of serial litigation, where opponents file lawsuit after lawsuit, raising new claims only after old ones fail. All claims should be consolidated into a single proceeding with a strict statutory timeline. Furthermore, courts must stop treating paperwork errors as construction emergencies. Currently, if a judge finds a flaw in an environmental review—even a minor one—the default remedy is to vacate the project’s permits and halt construction entirely while the agency goes back to fix it. This is needlessly destructive. Courts should instead adopt “remand without vacatur,” a standard already common in federal administrative law: order the agency to correct the error, but let the project continue while they do. The building keeps rising; the paperwork catches up.

Finally, we must stop subsidizing obstruction. The current system creates a perverse risk asymmetry: plaintiffs can recover their legal fees if they win, but rarely pay if they lose. This one-way fee shifting encourages speculative litigation by making obstruction essentially free. To balance the scales, we should require plaintiffs to pay the defendants’ legal costs when suits are found to be clearly pretextual, non-environmental, or filed by repeat abusers of the system. By introducing financial risk for bad-faith actors, we can force opponents to think twice before using the courts simply to impose delays.

Reforming the legal system is a monumental challenge. The legal profession is politically powerful and invested in the status quo that enriches lawyers while empowering wealthy interests to block transit, housing, and clean energy. My research on the political economy of the bar shows that the United States is an outlier among developed democracies: American lawyers are the most numerous and highest compensated in the world, yet the U.S. simultaneously ranks a distant last in terms of ordinary citizens’ ability to access and afford civil justice. This self-regulation of the legal profession correlates not only with higher litigation costs but with greater economic inequality. If progressives and liberals can exploit the widening gap between the legal profession’s economic incentives (scarcity) and its political values (equity), regulating the legal profession would not only unleash growth but curb a major source of inequality.

VI. The Progressive Roots of the Abundance Agenda

The distortion of environmental law is emblematic of a much larger phenomenon. Housing is the most visible arena, but litigation slows growth everywhere. Fossil-fuel groups sue to halt wind farms, corporations manipulate patent law to block competitors, and infrastructure projects face routine delays through strategic lawsuits. In America, power expresses itself through litigation. If you can pull a legal lever, you can choke a project.

The fight against manufactured scarcity is not new. It is the modern incarnation of a battle that animated the first wave of American progressivism.

The Progressive-era economist Henry George argued over a century ago that the greatest threat to shared prosperity was the parasitic behavior of land speculators. He saw a class of people who produced nothing, yet profited enormously by monopolizing land and charging others for access. Their wealth came not from innovation or labor, but from passively owning a scarce resource and collecting the value created by the community around them.

The wealthy homeowner using environmental laws to block affordable housing is the modern heir to George’s land speculator. They use a privileged position—not just wealth, but access to a complex, expensive, and exclusive legal system—to hoard opportunity and choke off growth. Like the speculator, they profit from a scarcity they actively maintain.

The modern push for abundance is often framed as a break from progressive tradition. In reality, it is a return to it. Progressives typically defend regulation as a check on corporate power. But when the regulatory environment becomes captured by the wealthy—used to exclude the vulnerable and protect asset values—reforming that system is a distinctively progressive project.

The original aim of the Progressive movement was to break the power of entrenched interests—trusts, monopolists, and political machines—that used procedural advantages to stifle the public will. Today, the entrenched interest is not a railroad trust; it is a legal complex that allows private property owners to veto public goods.

While George’s solution was to tax the unearned wealth from land, our first step must be to dismantle the legal weapons that allow this modern gentry to protect their fiefdoms at everyone else’s expense.

It is clear that our permitting process is broken. But we cannot fix these problems without confronting their source: a legal system designed by lawyers, for lawyers, and exploited by the wealthy to manufacture scarcity. Permitting reform will only get us so far if litigation-friendly courts can simply reinterpret those reforms to preserve their own empire. A pro-growth future can be legislated into existence only to be litigated to death.

Henry George warned us a century ago that the greatest enemy of progress was the passive extraction of value by those who own the land. Reforming the legal system that primarily benefits modern gentry is not a betrayal of progressive values. It is a return to them.

I live in Austin, and the state is currently pushing through a massive multibillion-dollar expansion of I-35 that will widen the highway to up to 22 lanes right through the heart of our city.

As someone deeply invested in pro-urbanism, I find myself in a frustrating philosophical no man’s land regarding this project. On the merits, I despise it: it is a 20th-century relic that ignores the perfect opportunity for high-speed rail connectivity between Dallas, Austin, and San Antonio. Yet, while I disagree with the project, I am also deeply skeptical of the legalistic mechanism being used to fight it.

The lawsuit filed to block the expansion represents a fascinating, if uncomfortable, intersection of interests. In this case, I see pro-urbanists—who want density and transit—sharing a foxhole with the NIMBY coalition. But as Bonica shows, "regulation by litigation" framework is a net harm to the very goals urbanists should be pursuing.

By using the courts to "gunk up the system," we are validating a legal gauntlet that is far more often used to kill the projects we do want. When we lean into procedural fetishism to stop a highway, we are sharpening the same blade that wealthy homeowners use to decapitate housing density and transit lines.

The I-35 project is a terrible plan, but is it illegal? Probably not. We cannot build a future of abundance if every project, even the bad ones, is destined to be litigated to death.

We want our $80 trillion back!! (see HCR today). Tax the bloated rich and restore the money we earned and were cheated of. 45 years of thievery is enough.